Psychrometric Processes Explained for HVAC Engineers (With Formulas)

Psychrometric processes are the “moves” we apply to air in HVAC systems to control temperature and moisture. If you understand what changes during each process (DBT, RH, humidity ratio, enthalpy), you can size coils, estimate loads, and troubleshoot air-conditioning problems much faster.

This guide explains the most common psychrometric processes used in HVAC design, with the practical formulas engineers use daily and where each method is applied.

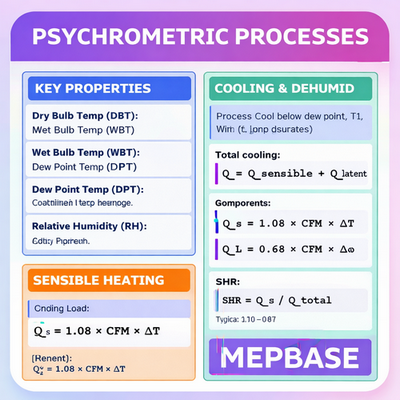

Key psychrometric properties (quick reference)

Before jumping into processes, here are the key properties you will see again and again:

- Dry Bulb Temperature (DBT): normal air temperature measured by a standard thermometer.

- Wet Bulb Temperature (WBT): temperature measured with an evaporating wet wick; useful for evaporative cooling and moisture evaluation.

- Dew Point Temperature (DPT): temperature at which condensation starts (air becomes saturated).

- Relative Humidity (RH): how “full” the air is with moisture relative to saturation.

- Humidity Ratio (ω): mass of water vapor per mass of dry air (moisture content).

- Enthalpy (h): total heat content of moist air (sensible + latent).

Common HVAC relationship (Imperial): Sensible heat is often estimated using:

- Qs = 1.08 × CFM × ΔT

Latent heat (moisture change) estimate (Imperial):

- QL = 0.68 × CFM × Δω

Note: The constants 1.08 and 0.68 are commonly used in Imperial HVAC calculations and are based on standard air conditions. For high accuracy (different altitude/air density), use psychrometric software or corrected air properties.

Sensible heating (temperature increases, moisture stays the same)

Process: Heat is added to air without adding moisture. This means the air gets warmer but the moisture content does not change.

Typical formula (Imperial):

- Qs = 1.08 × CFM × ΔT

What changes during sensible heating:

- DBT increases

- Humidity ratio (ω) stays constant

- RH decreases (warm air can hold more moisture, so RH drops)

- Enthalpy (h) increases

Where it’s used:

- Winter space heating

- Preheat coils (before humidification)

- Reheat coils (after dehumidification to control supply air temperature)

Sensible cooling (temperature decreases, moisture stays the same)

Process: Heat is removed from air without removing moisture. Air becomes cooler, but moisture content remains unchanged.

Typical formula (Imperial):

- Qs = 1.08 × CFM × ΔT

What changes during sensible cooling:

- DBT decreases

- Humidity ratio (ω) stays constant

- RH increases (cooler air holds less moisture, so RH rises)

- Enthalpy (h) decreases

Where it’s used:

- Sensible cooling coils (when coil surface temperature is above dew point)

- Night cooling strategies

- Pre-cooling in dry climates (when dehumidification is not required)

Cooling and dehumidification (remove heat and remove moisture)

Process: Air is cooled below its dew point temperature so water vapor condenses out. This is the most common process in air-conditioning because it reduces both temperature and humidity.

Total cooling:

- Qtotal = Qsensible + Qlatent

Component formulas (Imperial):

- Qs = 1.08 × CFM × ΔT

- QL = 0.68 × CFM × Δω

Sensible Heat Ratio (SHR): SHR tells how much of the total cooling is sensible (temperature change) versus latent (moisture removal).

- SHR = Qs / Qtotal

Typical SHR range: ~0.70 to 0.85 (depends on building and climate).

What changes during cooling & dehumidification:

- DBT decreases

- Humidity ratio (ω) decreases

- RH may increase toward saturation near the coil (then controlled by leaving conditions)

- Enthalpy (h) decreases significantly (sensible + latent removed)

Where it’s used:

- AHU / FCU cooling coils

- Fresh air treatment units

- Summer air-conditioning and humidity control

Engineer tip: If the coil leaving air is too cold, systems often add reheat to control supply temperature while still removing humidity.

Engineer shortcut: To calculate SHR, enthalpy change, and moisture removal accurately for cooling coils, use the MEPBase Psychrometric Calculator instead of manual chart plotting.

Humidification (add moisture to air)

Process: Moisture is added to air, either with steam (adds heat) or with adiabatic methods such as water spray (evaporative, often cools air slightly).

Steam humidification

Process: Adds moisture and typically increases temperature slightly.

Moisture addition (rule-of-thumb form):

- ṁw = (CFM × Δω) / 60

Adiabatic humidification (spray/fog)

Process: Water evaporates into air. DBT can drop slightly, moisture increases, and WBT is often close to constant.

Where it’s used:

- Winter conditioning in dry climates

- Clean rooms and laboratories (humidity control)

- Museums and hospitals (comfort + preservation)

Mixing of air streams (fresh air + return air)

Process: Two air streams mix (example: outdoor air and return air). The mixed condition is a mass-weighted average of the incoming streams.

Mixed air temperature (concept)

- Tmix = (ṁ1T1 + ṁ2T2) / (ṁ1 + ṁ2)

Mixed air humidity ratio

- ωmix = (ṁ1ω1 + ṁ2ω2) / (ṁ1 + ṁ2)

Where it’s used:

- AHU mixing box (return + outdoor air)

- Economizer mode (free cooling)

- VAV systems and fresh air compliance

Engineer tip: Always check mixed-air condition before coil selection. In hot climates, outdoor air can dominate the coil load.

Evaporative cooling (cooling by evaporation)

Process: Water evaporates into air. This reduces DBT while increasing humidity ratio. Wet-bulb temperature is approximately constant (especially for direct evaporative cooling).

Temperature drop estimate:

- ΔT = ε × (DBT − WBT)

Typical effectiveness (ε): ~0.7 to 0.9 (varies by equipment type).

Types:

- Direct evaporative cooling: typically 70%–80%

- Indirect evaporative cooling: typically 50%–70%

- Two-stage systems: often 90%–95%

Best for:

- Hot, dry climates

- Low RH conditions (for better temperature drop)

Dehumidification (remove moisture from air)

Process: Moisture is removed from air either by cooling below dew point (condensation) or using desiccants (chemical absorption/adsorption).

Cooling-based dehumidification

Air is cooled below dew point so water condenses and drains away. This is the most common method in comfort AC.

Desiccant dehumidification

Moisture is removed using a desiccant wheel or chemical media. Often used when very low humidity is required.

Moisture removal rate (Imperial style):

- ṁw = 0.68 × CFM × Δω

Where it’s used:

- Swimming pools (high latent loads)

- Ice rinks

- Supermarkets and cold rooms (humidity control)

Quick checks HVAC engineers should remember

- If DBT changes but ω is constant, it’s a sensible-only process (heating or cooling).

- If ω decreases, moisture is being removed (dehumidification / cooling below dew point).

- If ω increases, moisture is being added (humidification / evaporation).

- High SHR means mostly sensible load; low SHR means high latent load (humidity problem).

Frequently asked questions (FAQ)

What is the difference between sensible and latent heat?

Sensible heat changes temperature (DBT), while latent heat changes moisture content (humidity ratio ω).

Why does RH drop during heating?

Because warm air can hold more moisture. If moisture content stays the same (ω constant) and temperature increases, RH decreases.

What does SHR tell you in HVAC?

SHR shows how much of total cooling is sensible. It helps you understand whether your load is mostly temperature-driven or moisture-driven.